By: Justin Dalaba

This month, we sat down with Mark Whitmore, a well-versed forest entomologist and Director of the New York State Hemlock Initiative. The Initiative has a full team of researchers who “work with their souls” to conserve hemlocks. Why would New York’s third most common tree need saving? A forest pest no bigger than a strawberry seed, Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA) or Adelges tsugae, is decimating populations of this iconic and climax tree species with a long list of species that depend on it, including us.

“My specialty is in biological control of forest pests,” or more specifically, Mark currently focuses on predators from the Pacific Northwest to help control HWA originating from southern Japan. Mark’s interest in biological control takes him back many years, starting with the Balsam Woolly Adelgid in the Pacific Northwest: a sister sap-sucking insect to HWA. Growing up in rural Washington state, Mark started out studying botany and plant physiology. “As I was spending my summers working in the woods, I noticed there was a stand of alpine fir trees dying on the south side of Mount Baker.” What he found was an invasive species that has since dramatically changed the Cascades, and perhaps his mission too. With limited funding and support for the invader at the time, Mark took a side step to study bark beetles in graduate school (a native forest pest), before ultimately dedicating his career to safeguarding Northeast forests from the destruction he saw in the Pacific Northwest.

“My specialty is in biological control of forest pests,” or more specifically, Mark currently focuses on predators from the Pacific Northwest to help control HWA originating from southern Japan. Mark’s interest in biological control takes him back many years, starting with the Balsam Woolly Adelgid in the Pacific Northwest: a sister sap-sucking insect to HWA. Growing up in rural Washington state, Mark started out studying botany and plant physiology. “As I was spending my summers working in the woods, I noticed there was a stand of alpine fir trees dying on the south side of Mount Baker.” What he found was an invasive species that has since dramatically changed the Cascades, and perhaps his mission too. With limited funding and support for the invader at the time, Mark took a side step to study bark beetles in graduate school (a native forest pest), before ultimately dedicating his career to safeguarding Northeast forests from the destruction he saw in the Pacific Northwest.

In discussing Mark’s current research focus, he responded “my questions are numerous, the answers are sometimes hard to come by, but it’s really important to answer the questions so we can develop management strategies to mitigate the impact of these invasive species in our forests.” When it comes to big “game changer” pests like the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid and Emerald Ash Borer (EAB), Mark says “we need to understand them in order to be more effective in our implementation of classic biological control.”

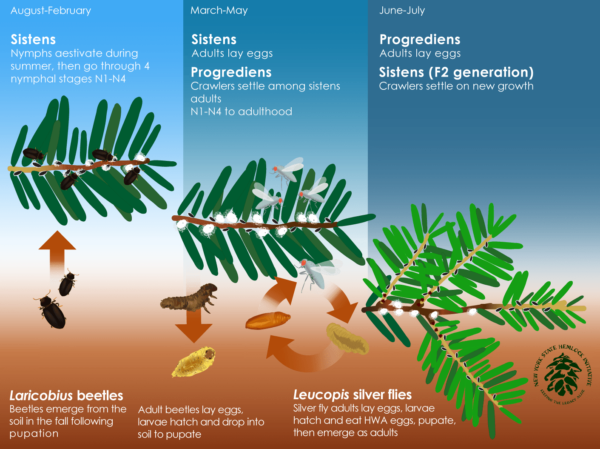

One of the key problems Mark’s team is working on relates to the HWA’s bivoltine reproductive cycle, where they produce two generations each year. This impressive aspect of their biology has allowed them to become such rapid and destructive invaders where they lack natural predators. To help control HWA, a predatory beetle (Laricobius spp.) was first released in the early 2000s. Mark explains the Laricobius beetles specialize on the first, or overwintering generation of HWA. “The problem is that with the second generation, we notice no direct impact on the overall numbers of adelgids.” The daughters in the second generation are actually more successful when fewer of their mothers are claiming space on the tree’s tissue.

“This is a recent revelation I think to the researchers, that we really need to look at specialists not only on the overwintering generation, but the second generation.” That’s where the silver flies (Leucopis spp.) come into play. A more recent addition to our set of allies, this predator specializes on HWA’s spring-summer generation, and was first released in hemlock forests in 2015. “It also happens that with our techniques of acquiring the predators from the Pacific Northwest, we get silver flies and Laricobius in the same ball of wax,” Mark explains.

“We’re lucky to have that tool in New York and in the Northeast because HWA is susceptible to cold temperatures,” a potential advantage when compared to more southern infested areas, including parts of the Appalachian, Blue Ridge, and Great Smokey Mountains. Mark’s decade-long research on overwintering mortality has found that in years like this one, some sites in New York have over 90% mortality of HWA. The problem lies in the years between, when fewer cold spells and low mortality “allowed populations just to explode and expand across the landscape.” Mark continues, “I think one assumption we can make with climate change is that we’re not going to see these cold events as often and as severe in the past, and that will definitely benefit the adelgids and their spread.”

So how will we know whether these biological controls are successful in the long-run? According to Mark, the hardest aspects of biological control are “determining establishment and evaluating spread in real time.” The only way to determine success and maximize biocontrol investment is through population build up and spread from the release sites. “Using eDNA, we’ll be able to do that,” a novel technique that Mark’s team recently adopted through collaboration with the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability. This technological advancement replaces the standard, extremely time-consuming technique of manually clipping hemlock branches and observing them under a microscope.

“At the time, there were very few instances of terrestrial use of eDNA to detect species, and certainly there were none related to the detection of predators that are released.” Mark says they’ve honed the technique such that “we are actually able to detect very low levels of HWA, which is really important in areas like the southern Adirondacks, where populations are just expanding right now.”

Looking back to the West offers Mark some hope. “I don’t see any impacts of HWA in the West because it has a huge predatory complex associated with it, and hopefully that gives us the impetus to really work harder out East to implement biocontrol.” Mark’s team relies on the support of state agencies, land owners associations, and private individuals to implement management.

“I want to save the hemlocks. It’s pure and simple. And hopefully our work on biological control will go a long way to doing that.” Mark adds, “I have hope, and without hope you have nothing.”

To learn more, visit: https://blogs.cornell.edu/nyshemlockinitiative/